It sounds like an adventure story and it is, only this is an epic not experienced by Harry Potter but the backdrop against which our lives are being played out.

I recently attended a conference in Frankfurt that highlighted some of the main economic issues of our times. Surrounded by the gleaming towers of the Deutsche Bank, the Sparkasse and the ECB a lot of things came into perspective during an enlightening session of speeches delivered by leading economists who were not only knowledgeable but also passionate and capable of placing it all within the wider context of society.

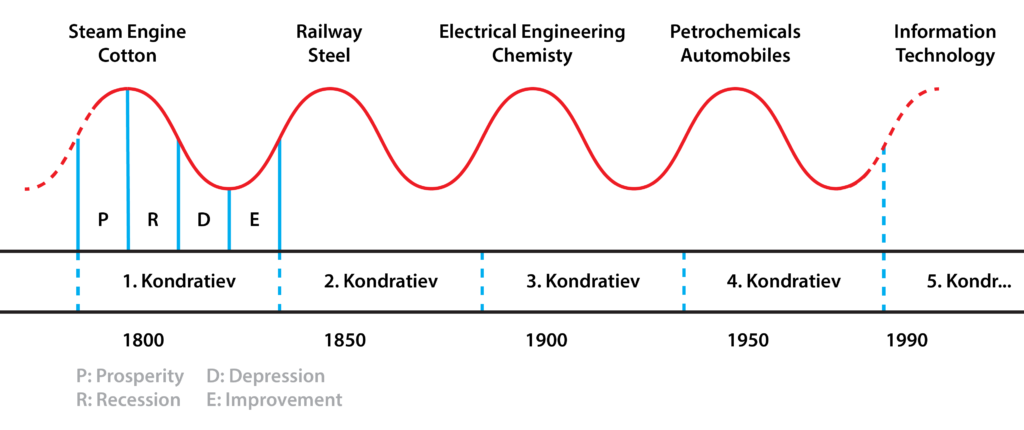

It is against this background that I became reacquainted with such concepts as financial repression and the K-waves named in honour of Nikolai Kondratiev, a far-sighted Russian economist executed by Stalin for proposing a view of how economies work that was in conflict with Marxist doctrine. Today, however, Kondratiev’s theories have once again been put in the limelight by the most recent economic crisis.

Financial Repression

The financial crisis, or tumbling house of cards that precipitated the sovereign debt crisis involving not only the Euro zone but in reality most developed economies, has led to a return to financial repression. Done away with by the Reagan administration, it basically means a return to a strictly regulated environment in which governments manipulate financial mechanisms to speed up the process of public debt reduction.

In an environment in which painful public sector cuts and tax hikes are highly unpopular, financial repression acts as a form of stealth tax that redirects funds towards government. At the heart of the mechanism is the creation of a differential between interest rates and inflation that leads to negative real interest rates, which in turn lower the cost of servicing government debt and reduce the debt in real terms.

The measures used by governments and central banks to achieve this include setting very low base rates, establishing capital controls over the flow of money in and out of the country, exerting far more control over banks and other financial institutions, and forcing the latter to increase their reserve requirements (cash to loan ratios) and capital requirements (cash to asset ratios). In the process, the public debt is also domesticated, as governments reduce their dependence on foreign lenders and force national institutions to buy their low-yielding or even negative interest bonds.

The losers are savers (the suppliers of investment capital), who see their money eroded while governments, businesses and individuals who spent and borrowed freely are ‘rewarded’ by not having to face the full responsibility for their indebtedness. Unpleasant as this is it does create the stabilising conditions necessary for economic recovery, which leads us straight to Kondratiev.

The 6th Kondratiev

When looking back, Nikolai Kondratiev observed a long-term pattern within which the shorter cycles played themselves out over a period of 40 to 60 years. Named in his honour by Schumpeter, these K-Waves describe a cycle of ascent, climax and descent triggered initially by the accumulation of technological breakthroughs that together act as a catalyst for a whole new phase of growth and development.

1. Growth

According to my own understanding, this initial spark leads to increasing investment, innovation, economic growth, output, earnings and eventually inflation. Interest rates rise too during this period of real dynamic growth, which eventually gives way to a phase that has been described as ‘frenzy’ by economist Carlota Perez.

2. Frenzy

This part of the cycle is characterised by a ‘heating up’ of the economy during which huge inputs of capital and resources rather than real innovation and demand propel growth. Prices bubble, supply overshoots demand, leading in turn to over-production, intense competition and an inefficient use of capital and other resources, as well as lower returns and cheap credit.

3. Recession

Essentially the reserves built up during the first phase are pumped into the second one. However, they only serve to stave off the inevitable, and in doing so intensify the ensuing collapse and resulting recession or even depression. The dramatic event usually takes the form of a stock collapse and/or financial crisis such as those of 1929 and 2008, and the resultant downturn is far more intense than the shorter cyclical ‘breathers’ we’ve become accustomed to.

One of the results of the second period’s spending spree that becomes strongly manifested now is chronic indebtedness. Once the bubble bursts and the music stops playing the dire state of things suddenly becomes clear. Production, employment, earnings and investment drop sharply, consumer confidence melts away and people begin hoarding their money as the flow of money slows down further. Low inflation (or even deflation) are offset by even lower interest rates to produce negative real interest rates as governments attempt to bring their debt under control and restore confidence

4. Recovery

It has by now become clear that the former drivers of the economy have matured, so these sectors are scaled down, receiving far smaller resource inputs amid a painful but necessary restructuring that sees supply brought in line with a demand that is low but building up pent-up energy. Tight financial control and debt reduction combine with cheap credit and lower cost levels to create the conditions for gradual recovery.

I believe this is the stage we are in now. A lot of business and public sectors are putting their house in order. Confidence in the core mechanisms of our economies is slowly returning, releasing unsatisfied demand and investment, and thus stimulating the circulation of money. What’s more, financial repression is forcing those with savings to make their money work for them, and so the conditions for a resumption of moderate growth are set.

1. Growth?

The big question, however, is whether we are about to hit the beginning of another big growth cycle. According to Kondratiev’s theory we should be, and this would mean the beginning of a whole new innovation-led boom that should last for some time. The first five Kondratievs identified so far describe modern economic history from the steam and textile-driven industrial revolution of the late 18th century (1) to the steel and railway booms of the mid-19th century (2), the electrical and chemical engineering boom of the early 1900s (3), the post-war era of the petrol-driven automobile (4) and the electronic and IT boom that peaked in the 1990s and had its frenzy years in the 2000s.

If we’ve just seen the implosion of the 5th Kondratiev and are still struggling to emerge from its debris, then surely the 6th Kondratiev is about to begin? Theoretically yes, and while electronics still has a long way to go before it runs out of innovation potential, it is believed that the next great technological catalyst will be linked to our need to balance our needs with the world we are developing and damaging at a faster rate than ever before. Population growth combined with increasing per capita consumption is nullifying the more moderate gains in efficiency, so in the coming decades we will need quantum leap advances in how we manage precious resources ranging from fuel, energy and land to the very air we breathe. Now this could be a Kondratiev to look forward to!